If you’re interested in advertising effectiveness but have never heard of Dr Grace Kite, we can’t judge you. We didn’t know about the founder of analytics consultancy Gracious Economics, either – and she’s spent two decades working in a field that we like to think we pay pretty close attention to. Shame on us.

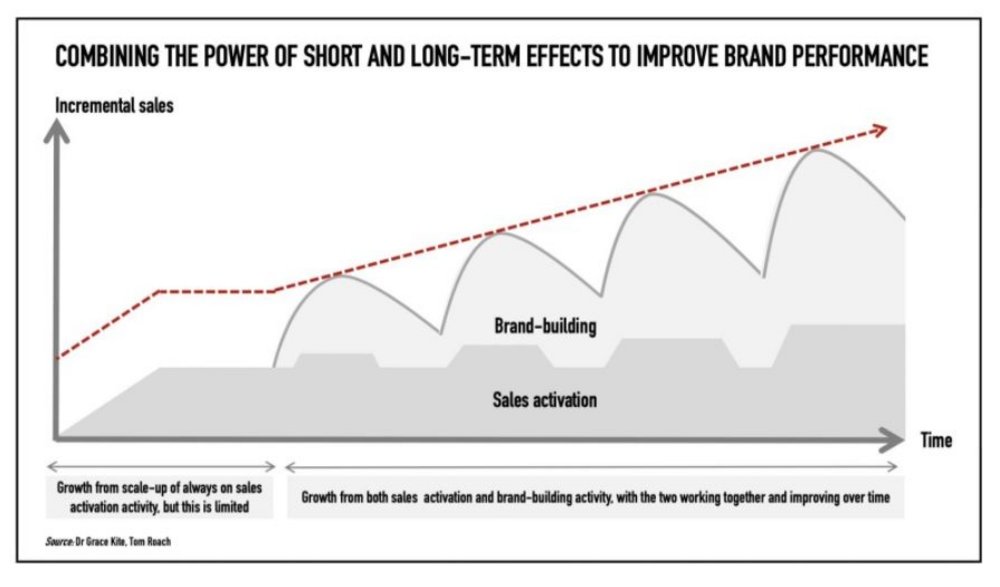

But in the summer, Kite caught our attention with a blog about Les Binet and Peter Field’s graph depicting the effects of long-term and short-term advertising on sales (you know the one).

‘The truth is that although the chart is right about how advertising works, it’s often wrong about what the real world looks like,’ wrote Kite, who then used decades of sales data to show the messy reality of how short- and long-term effects combine to improve brand performance.

Source: Dr. Grace Kite

Source: Dr. Grace KiteA couple of months later, Kite published another piece. This time she was advancing her theory that some online display ads act more like signposts, guiding customers to a purchase they were already inclined to make, than sales drivers.

Again, it was a fresh and well-supported perspective that mixed theory and practice to explain how advertising works. Our interest was piqued.

At this point we thought we should probably just get on the phone, and Kite agreed to answer some of our questions about her work and her thinking. Below is an edited account of that interview.

Put as simply as possible, what does Gracious Economics do?

Put really simply, what we do is we analyse data to see whether advertising and marketing is working, and then, within that, which types work best.

So we give clients advice, and the advice we give is things like: ‘If you want to sell more of your stuff, do more in TV and less in newspapers, use this creative and not that one.’ Those are the kinds of advice that we give.

Source: Contagious

Source: ContagiousHow has the advertising industry's relationship with analytics and data has changed in the two decades that you’ve been practising?

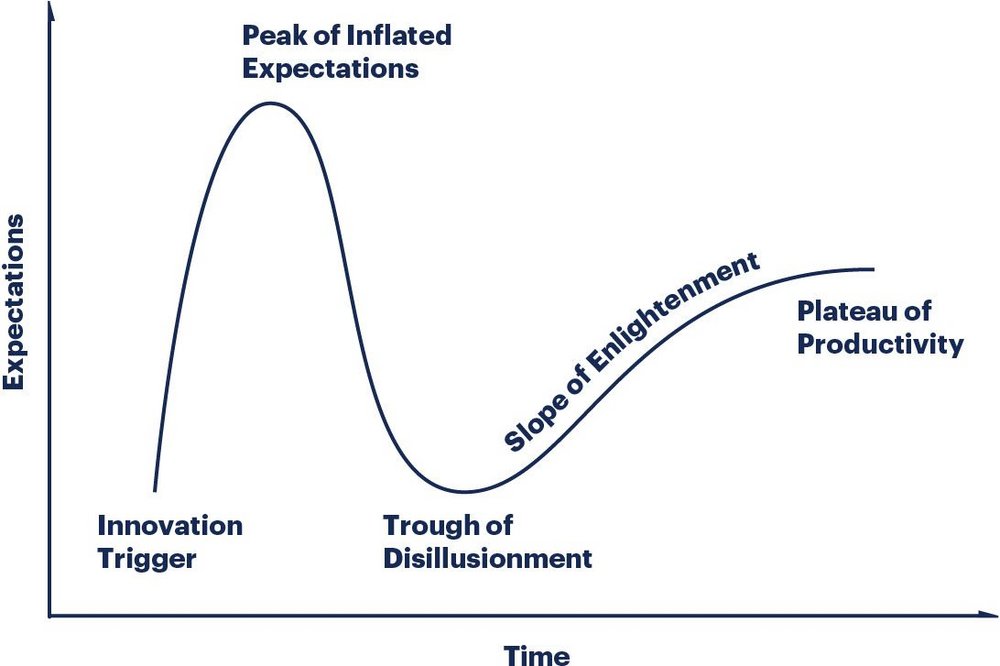

You know the Gartner Hype-Cycle? I’ve watched that play out over the last two decades. [Analytics are] like any other new technology: When it's launched, there's a huge excitement about what we might be able to do with it, and then there's this point afterwards when people realise that the reality of it isn't quite as good as the hype. And eventually, there's a middle ground, they call it the plateau of productivity, where it just works. It doesn't do everything that was hoped for in the beginning, but it works, and people can learn from it.

What’s really interesting about marketing analytics is that different techniques have come and gone through those various stages but very few of them, even after 20 years, are on that plateau of productivity.

Even though data has made people much more informed, it's actually made life more difficult for marketing directors and CMOs. Data isn't their first love. They've got this long to-do list, most of it to do with managing people or agency relationships, or understanding consumers. All this data data is flying about, but it's still not reached that point where it's easy to digest and use, and it’s actually quite stressful.

We did some research last year with marketing directors and what they said was that it's often very tech-y people doing econometrics work. These people care about the tools and the equations, but the marketing directors and CMOs don't care about all that stuff. They just want to know how to do their job better.

Analytics doesn't lead to change if people don't make it palatable for marketing directors and CMOs to use. And in our experience, analytics only leads to genuine change when it has a human face. A lot of analytics work gets done and never acted on, just because it's too hard for people to go from what they're given, which is all this tech-y stuff, to something they can actually put into practice.

What’s a common misconception you encounter from clients, either about analytics or how advertising works?

There's this dominant narrative that people do too little brand advertising and too much activation, and I don't see that in the clients I work with. I think there are as many clients who are doing too much brand work as there are clients doing too much activation. So, you meet some [marketers] that are all-in on brand and they're generating demand that is not being harvested properly.

Brands are often accused of getting the balance wrong because of the pressure they face from shareholders to make profit quickly, which leads them to do more activation work. What kind of factors do you think force a brand to go too hard on brand building?

It can be that you get one person who is a big brand believer, and that person has got into the CMO role. So it can be individual personalities. And it can also be that organisations are risk averse. When you look at the big five banks in this country, they’re really heavy spenders on brand. They are each spending so much on brand advertising because they know that their brand is valuable and they don't want any of the others to get ahead of them.

What do you think is the most significant thing that the age of data has revealed about how advertising works?

For me, it's the really simple one. It's that data has revealed that advertising does work – that it can be accountable, that it does produce a return and that it can be put alongside other investments that a business might make.

I know that might seem like an obvious one to point to, but it's such a powerful thing that CMOs have now and they didn’t before.

They can rock up to the board now and say, ‘Look, if you give me this budget, I can invest it and give you this many sales, this much revenue, this much profit’. And finally, marketing is able to take its true role as an engine for growth in businesses.

Source: Dr. Grace Kite

Source: Dr. Grace KiteI think a lot of people in this industry would argue that the increase in data hasn't led to a commensurate increase in advertising effectiveness. Do you agree with that?

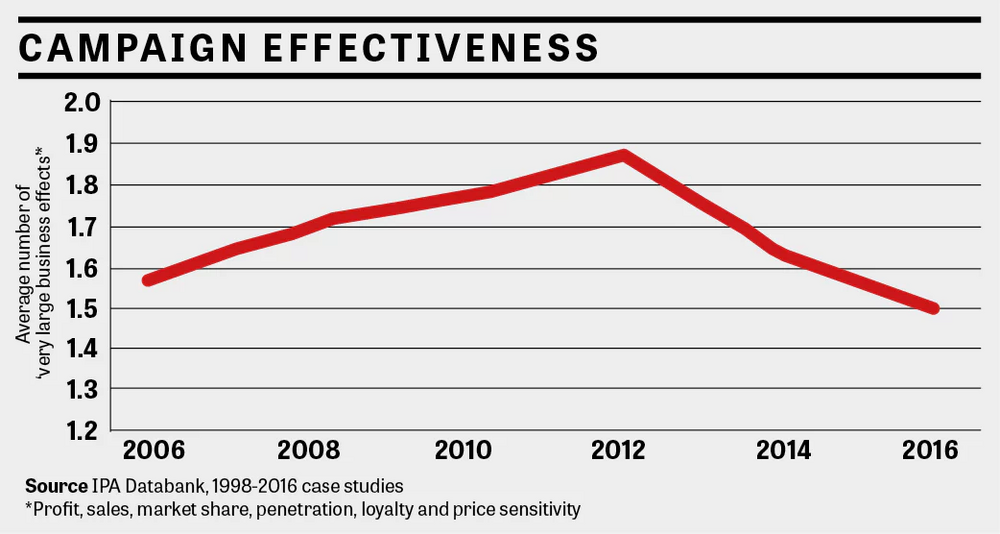

People do argue that, don't they? That we haven't seen an increase in advertising effectiveness in general, and maybe that advertising effectiveness has been in decline over the last five or 10 years. But actually, the evidence base for that claim is really, really weak.

I'm an empirical person first, and I would say that we just don't know whether that is a fact or not. And we need to really assess whether it is. Because if it's a fact, it's very alarming. But if it's not, we're worrying about nothing.

And what's interesting is that in the period when data has expanded, digital advertising has expanded massively as well. So the two things have kind of gone hand in hand a bit.

And people tend to argue that effectiveness has been falling because people [do too much] digital and activation. But I'm unsure whether it's true or not. You could argue that people doing lots of digital activation has better harvested demand than in the past. So it's to be confirmed, really. And actually, I'm quite excited about this: it's my mission for 2021 to tackle that exact question: is effectiveness on the decline or not?

I’m working with a load of other friends in the industry who have agreed to help. We’re putting together everybody's return on investment database. So Omnicom is in and we’re talking to Group M and WPP, and the IPA are hopefully going to be involved, too. The idea is that we're going to get all of those ROI from different campaigns that have been evaluated everywhere, put them together and say, ‘Is ROI is declining or not?’

At the moment all we know is that in the IPA databank there are less people claiming very big business effects, and that’s a pretty weak evidence base to make this big claim that effectiveness has been falling. And I think we just need to know, as an industry.

What’s the most surprising finding that your data analysis has revealed about a client's business or customers?

One of the things I've always found interesting is the opportunities that are available to advertisers when the outside world is changing.

Return on investment for advertising is really quite a lot higher if you are on the right side of change in the real world.

For example, at a time when a lot of young people were starting to buy their clothes online, you could see a huge return on investment when asking young people to buy their clothes online. Whereas you’d see a much weaker return on investment when asking people to buy their clothes in the shops. And that kind of pattern is happening in every category.

But I think it's one of the things that people don't think about enough when they're planning. They think a lot about that brand and what it can offer, they think about the competitive landscape. But they don't always think about the underlying trends and how the world is changing.

Is there practice or metric that’s gets used a lot that you wish would just die?

Do you mean in terms of [social media] likes? No. I think anything that can help marketers to go from not knowing to knowing something is worth having. And I quite like my LinkedIn likes. They make me happy.

What are the most exciting area of research for you right now?

I think cross contamination is where the exciting, fertile areas are. There are potentially two different camps in marketing: Your big-brand-do-a-TV-ad-creative-agency group and the watching-the-dashboard-optimising-for-SEO-buying-search-ads group. You might say it's offline versus online advertisers. Or maybe you'd say traditional advertisers and performance marketers – but you know what I mean.

And the really interesting marketing people that I talk to, where I just want to talk to them all day, are the ones where they've come from either camp but they've crossed into the other.

So the performance marketers that are thinking about TV and thinking about demand, and are learning from brand advertisers – they're the wise ones. And the same with the planners who are interested in what online data can show them and incorporate that into what they're doing – they're the wise ones, too.

I think, more and more, those two camps are starting to overlap. And I think it's a really fertile ground for learning about how to be good at marketing. And in the future, that combination of the two skill sets will be more than the sum of its parts.

We [Gracious Economics] try to sit at that crossroads in the way we do analytics as well. We've got an algorithm that uses search data to give a really quick overview of a category: what people want, what people search for most, what kind of what kind of aspects of the products are most important. And that is just really useful for somebody building a brand campaign. And that’s just an example of going from the performance marketers knowledge and seeing what it can bring to the brand marketers’ toolkit. And we've also got stuff that takes us from the brand advertiser toolkit and applies it to performance marketing. It’s just such a fertile ground. And that's what I'm excited about.

What do you think about the levels of data literacy in the ad industry? Do you think everyone should know a little bit about econometrics?

I would say, no. I’m totally okay with creative people not being able to use a spreadsheet because I don’t know how to design a logo or shoot a film, and I don’t think anyone should expect me to be able to do so! People should just be able to be who they are. People go into advertising because it’s a creative industry and they don’t have to deal with spreadsheets, and it would be a shame to lose that.

What’s a good starter resource for anyone who did feel inclined to learn a little bit about analytics and econometrics?

For anyone thinking of commissioning econometrics or analytics, or who needs to use the findings, the best reference is called econometrics explained and it’s written by Louise Cook, who is a friend of mine and is very wise. That’s the thing to read.

Source: contagious.com