Coca-Cola did not create the legend of Santa Claus. The maker of the world’s most famous soft drink explicitly states this on its website. One can argue about this a little - it may be true that Santa Claus as a character did not originate in Coca-Cola’s marketing department, but on the other hand, we need to look at how most of us imagine Santa. The image of the big, bearded and warm-hearted grandfather is in many ways attributable to the American mega-corporation (although even in this case it was not the first entity to use it). For example, Santa owes Coca-Cola popularisation of his traditional colours – white and red. Before 1931, he wore them only sporadically. And indeed, Santa often looked different in his “pre-Coke” period than he did in his “Coke” period.

Christian symbolism with a Dickensian facelift

Today, it is essentially a historical consensus that the figure of Santa Claus is in many ways inspired by the Christian legend of St. Nicholas. He is said to have lived in 4th century ancient Greece (and today’s Turkey), specifically holding the office of bishop in the city of Myra. In the legends, he is often associated with charitable work against poverty and slavery, and it is from this tradition that the generosity of modern Santa is derived. One story, for example, tells how he gave three poor daughters a dowry instead of their father, thus preventing them from becoming prostitutes.

If we rewind the calendar many years to medieval Europe, we come across a tradition related to 6 December that is well known in the Czech Republic. Originally, children would put their shoes behind the door on that night, and St Nicholas would give them gifts overnight according to the tradition – they usually got silver coins. The German religious reformer Martin Luther was one of those responsible for making St Nicholas popular. But he shifted the gift-giving to Christmas, driven mainly by a desire to promote Jesus Christ rather than glorify the saints. Thanks to Luther, the idea of a mythical figure bringing presents to children at Christmas has become commonplace.

Father Christmas, however, has more roots in 16th century English folklore. At that time, the feast of St. Nicholas was less important for the English. It was generally accepted that the reason for the holiday cheer did not come until 25 December each year. Under the reign of Henry VIII, Father Christmas was depicted as a large man who usually wore green or scarlet robes. A further substantial revision occurred during the Victorian era, when some of the most famous writers of the time used the character in their works. His appearance was by no means settled, yet John Leech’s illustration for A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens is particularly memorable in this context. It depicted Father Christmas as a relatively fit man dressed in a green fur coat.

At this stage, it was clear that the image of the future Santa Claus was consolidating, yet he was still far from the image associated with him today. And above all, at that time he was obviously not yet associated with the marketing of any brand. But he had already come quite a long way from being a religious icon to a sort of pop culture symbol. But his modern image began to take shape in the 1860s in the biggest cultural melting pot of the time, America. Most memorable are Thomas Nast’s illustrations for Harper’s Magazine, in which Santa is depicted as a jolly, stocky bearded man who smokes a pipe and always has a sleigh pulled by his trusty reindeer team at his side. Even back then, he would pull on a red and white outfit from time to time, but it still wasn’t the only thing available in his wardrobe.

That changed in 1915, which is generally accepted as Santa’s marketing debut. However, it wasn’t Coca-Cola that was at this turning point, but another major soft drink manufacturer in America at the time, White Rock Beverages, which used Santa as we know him in its photographic advertisements for mineral water. The company built upon this experience in later years, and the figure became quite firmly established in White Rock Beverages’ marketing. However, it was coming up to the year when Coca-Cola took full advantage of him.

Rebranding with Santa Claus

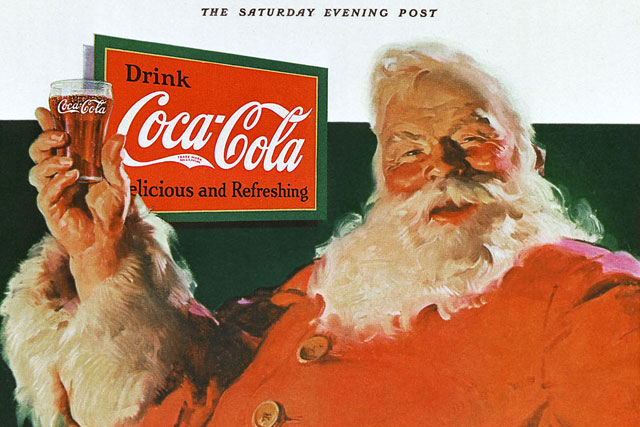

Thirst knows no season. This was a claim that Coca-Cola wanted to get into the public consciousness in the early 1930s. The popular product had been on the market since 1886, enjoyed extreme popularity and played a socio-political role in the context of the historic anti-alcohol movement. However, the carbonated soft drink, based on a recipe by Colonel John Pemberton, suffered from the fact that it was perceived primarily as a refreshing drink for the summer months. Coca-Cola’s advertising agency at the time – D’Arcy Advertising Agency – was doing everything in its power to change this prejudice, and the figure of Santa became a very convenient and powerful tool for them to kick-start this paradigm shift.

It was basically a happy accident. In 1930, the company enlisted the services of Fred Mizen, who drew an illustration of Santa drinking from a Coca-Cola bottle in the aisles of the Famous Barr Co. department store in St. Louis. This illustration was intended primarily for the period press, but no one anticipated the massive response this seemingly unassuming image would generate. It was so favourable that D’Arcy, led by its CEO Archie Lee, decided to use the same symbol in 1931. And then in many years to come.

First it was necessary to unify the image of Santa. This difficult task was undertaken by Haddon Sundblom, a Michigan-born illustrator with Dutch roots. His greatest inspiration was the poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, published in 1822 by the American poet Clement Clarke Moore. Sundblom decided to use this depiction of a Christian saint as a model for his Santa Claus - one who is warm, likes to laugh and generally comes across as someone you would like to spend Christmas with. A fitting bonus was the fact that St. Nicholas was described by Moore in his red and white bishop’s vestments, which was obviously a major value added for Coca-Cola.

Sundblom’s real-life model was his close friend, retired door-to-door salesman Lou Prentiss, who died in the course of the work. The illustrator then painted from his own image in the mirror and later began to rely on photographic records. However, Sundblom continued to refine the likeness of Santa Claus over the years, with the last authorial revision in 1964. Coca-Cola, however, actively used the visual for much longer. The originals of these drawings are still regarded as highly prized works of art today and have been so honoured to be exhibited in the world’s most famous galleries in Europe (the Louvre in Paris, the NK Department Store in Stockholm), Asia (the Isetan Department Store in Tokyo) and, of course, locally in America (the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago). But the home of most of them is Coca-Cola’s headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia.

Santa’s trucks arrived after the polar bears

It is perhaps surprising that Coca-Cola has not been very active in audiovisual advertising in the run-up to Christmas for a long time. No doubt it has also affected Santa, who has remained a Christmas symbol for the brand since his debut, particularly in the print advertising environment. This changed with the arrival of the 1990s. In 1993, Coca-Cola aired its first Christmas TV commercial, but without Santa Claus’s direct involvement. The spot was called Northern Lights and starred a pair of polar bears watching the Northern Lights while sipping Coca-Cola from a glass bottle. The ad was a big hit, but what is a bit surprising is that it entirely avoided the global corporation’s most established Christmas symbol.

Video: Coca-Cola – Northern Lights (1993)

The first commercial based on the close relationship between Coca-Cola and Santa Claus came in no time. And even in this case, Santa does not play a central role in it, but it is so thematically linked to him that it does not really matter that much. In 1995, Coca-Cola Christmas trucks first hit the television screens, giving rise to a truly modern holiday tradition, at least in the Anglo-American culture. This truly historic Christmas marketing presentation was made by the creative studio Industrial Light and Magic, which at the time had already worked on huge film projects including the Star Wars and Indiana Jones, and the iconic Forrest Gump. This Christmas caravan has quickly become a symbol of Coca-Cola and is closely associated with Santa Claus because an “animated” version of the original Sundblom’s illustration decorates the back of every single Christmas truck. The illustration actually comes to life for a moment in the ad – to gesture for a celebration of peaceful Christmas holidays and toast to the season – how else but from a chilled bottle of Coke. Christmas symbols and decorations abound in this short ad, and to this day, it is still the epitome of a quintessentially American Christmas for many.

Video: Coca-Cola – Holidays Are Coming (1995)

However, the Coca-Cola truck fleet remains a Christmas harbinger to this day. It is a kind of sign that Christmas is really coming, which certainly evokes intense memories of childhood in many viewers, giving them the opportunity to return to this carefree period at least for a while. This was further enhanced in the second half of the 1990s when fantasy became reality. Santa trucks actually took to the roads and toured cities all over the US and in many European countries. When this ad suddenly disappeared from pre-Christmas broadcasts at the beginning of the new century, it did not go unnoticed and general disappointment prevailed. And so, in response to millions of requests from people claiming that there was no Christmas without Santa’s trucks, the iconic ad returned to the airwaves in 2007. It got a major facelift, but everything popular remained. Santa’s fleet thus proved to be immortal. And that’s how we still see it today.

Video: Coca-Cola – Holidays Are Coming (2020)

From a product mascot to a symbol of hope and kindness

No global giant of Coca-Cola’s size could escape the paradigm shift in Christmas advertising that was launched by the British chain of department stores John Lewis in 2007. In the wake of its groundbreaking Christmas campaign, we can see a move towards more narrative spots that are de facto short films and emphasise storytelling, strong protagonists and emotionally mature and believable plots. It is clear that Christmas trucks are iconic and timeless; on the other hand, they do not bring many of those modern qualities. In fact, they are an obvious marketing stunt. But Coca-Cola certainly did not intend to abandon tradition in its new Christmas presentations. And the tradition undoubtedly includes its version of Santa Claus and Christmas trucks.

For example, we can look at the advert for the 2020 Christmas season, directed by Hollywood actor and director Taika Waititi, which testifies that nothing is impossible at Christmas. Waititi tells a story of a father of a family who works on a wind farm and decides to make sure that Santa really does grant his daughter’s greatest wishes. He sets off on a challenging journey to the North Pole, driven by one goal – he must deliver his little girl’s Christmas wish to Santa. But the moment he arrives at Santa’s house, he realises that he has succeeded on one hand and failed on the other – he will not make it home in time to celebrate Christmas with his family.

Video: Coca-Cola – Have Yourself a Merry Christmas (2020)

It is at this pivotal moment that Coca-Cola turned its Santa and his Christmas trucks into something more than mere holiday mascots. Santa appears on the scene as a truck driver, offering a ride back home to a selfless dad. Santa makes it in time, not forgetting to give him a revised version of his daughter’s Christmas letter – in which she wishes especially that daddy would be home with them for Christmas. Santa is the deus ex machina of the story, a symbol of hope and miracles that really do happen at Christmas. This is a huge shift from the way Coca-Cola has used him in its marketing before. The mascot becomes a fully-fledged character whose role in the story is unquestionable and, above all, irreplaceable.

Santa Claus in all of us

We might like to cry out that the world needs more Santas like this! And you can be assured that this idea resonated in the marketing department of Coca-Cola. This concept materialised in the recent advertising campaign presented by the company before Christmas 2023. While Taika Waititi’s spot three years ago illustrated what makes Santa Claus unique – he is reliable, warm and, most importantly, selfless – the latest ad calls on each individual to cultivate these “Santa” qualities in themselves. And there is no better time of the year to truly understand how: through acts of belonging and kindness, we can improve the lives of our closest loved ones, as well as complete strangers with whom we come into contact every day.

This message is certainly not brand new in the history of Coca-Cola’s Christmas ads, but it is the first time it has been so strongly personalised. The view of a world where everyone not only can be but also is Santa takes the marketing strategy even further away from product presentation, though the Christmas truck cannot be avoided either. This message of kindness is all the more socially relevant because Coca-Cola is also one of the most influential Christmas advertisers of recent years, according to a survey by the British agency System1. The company’s last three campaigns have achieved a high score of 5.6 out of 5.9 in the agency’s evaluation, which speaks about its first-class ability to build a brand in a way that both fosters customer loyalty and is able to influence their opinions and (not only) consumer behaviour. Again, it achieves this without emphasising the sales and product aspects.

Video: Coca-Cola – The World Needs More Santas (2023)

The move to this new narrative marketing does not mean Coca-Cola is abandoning everything that has worked perfectly for it at Christmas in the past. The hiatus of Christmas trucks proved unfortunate as consumers missed them. So, while the company is fully embracing modern trends in Christmas marketing, it is also staying true to its older, product-focused presentation. Each year, following the John Lewis model, it presents a new Christmas story, but this is accompanied on air by a second campaign – a ride on Santa’s Christmas fleet. This puts the company in a very advantageous position where, on the one hand, it can show off its creativity and, on the other hand, it can explicitly present its favourite product, referring to the fact that the consumer wants it. Such a position is very unique in the advertising world and many brands can only be quietly envious of Coca-Cola.

Coca-Cola has therefore managed the Christmas transformation perfectly and confirms its position as a company that, even after more than a century and a quarter in the market, is capable of being not only a winner but a winner with a human face. In this case, that face is covered with a massive beard and adorned with a warm smile that often makes even those who do not exactly love Christmas feel warm. And so we come back to Santa’s predecessor, the Father Christmas of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, who showed Ebenezer Scrooge as vividly as Santa what the magic of Christmas is all about.

We all have a little bit of Ebenezer Scrooge in us. But we also have a little bit of Santa Claus inside – and at Christmas, we should do our best to make the most of that potential and work together to make this world a better place to live in.